Alan Ruiz, “Infrapolitics” at 1708 Gallery

Rachel Hutcheson

Currently on view at 1708 Gallery is Infrapolitics, a solo exhibition by Alan Ruiz (b. 1984, Mexico City, Mexico). The exhibition explores the integration of social and political issues through seemingly apolitical infrastructures. While the politics of infrastructure have been discussed in terms of urban planning and access to education, work, and affordable housing, “invisible,” yet life-sustaining infrastructures have increasingly become part of the public’s consciousness, particularly in light of the ongoing water crisis in Flint, Michigan. Ruiz foregrounds these normally unseen supporting infrastructures, moving between the scale of the city and that of the individual gallery: from highways and urban development, to electricity, airflows, and even glass. His practice combines a long history of institutional critique and conceptual practices with social activism to underscore the integral relationship between social politics and material infrastructures.

Alan Ruiz, INFRAPOLITICS, 2019. Exhibition view. Courtesy of the Artist and 1708. Photograph by David Hale

Infrapolitics begins by situating the history of 1708 Gallery as a site of gentrification in the current Broad Street Arts and Cultural District. Ruiz connects the present site with past violent urban modernization projects by including archival photographs of the construction of the Richmond- Petersburg Turnpike, now part of I-95. In 1955, the construction of the toll road demolished large portions of the adjacent Jackson Ward neighborhood and bifurcated the historically black community. Arrows inserted into the photographs show the path of the highway. According to this modernist urban planning, black populations and their local economies and histories were ultimately expendable in the name of coded “progress” that privileged the transportation needs of white citizens in the growing suburbs. Today, the desires of arts newcomers and upscale leisure enterprises take precedent over those of the existing communities in neighborhoods within Richmond’s Arts District, which include Jackson and Monroe Wards (where 1708 is located).

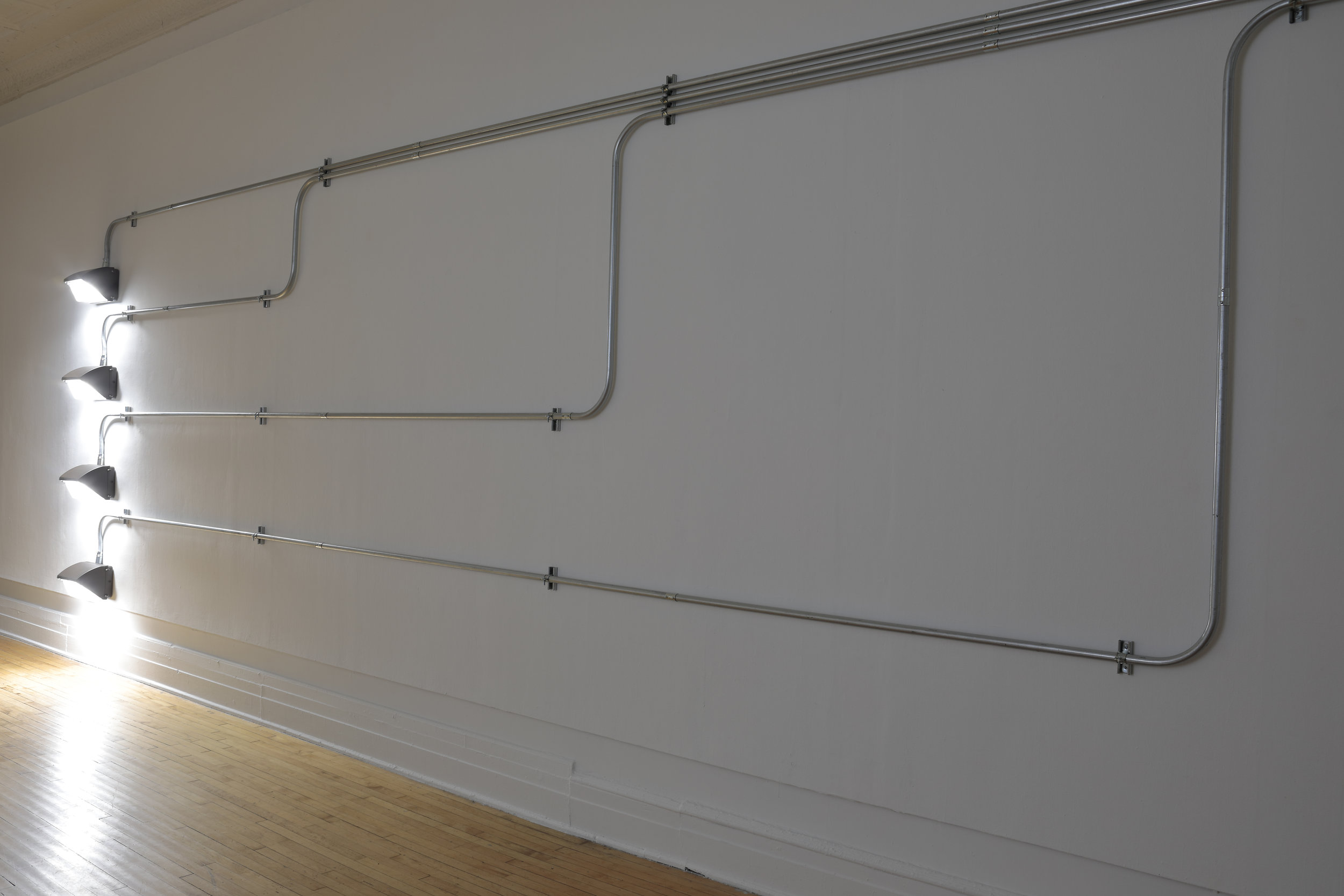

From the city’s infrastructure to the exhibition space, Ruiz’s works operate within traditions of institutional critique, such as those by Michael Asher and Hans Haacke, and the anarchitecture of Gordon Matta Clark by making direct interventions into the physical space of the gallery. The work Western Standards K80X4 redirects 1708’s electrical wiring from its hidden place behind walls and in the ceiling to instead snake along the walls.

Alan Ruiz, INFRAPOLITICS, 2019. Exhibition view. Courtesy of the Artist and 1708. Photograph by David Hale

This intervention conceptually and visually echoes Michael Asher’s seminal Kunsthall Bern (1992) which relocated all of the building’s radiators to the entryway, the steel pipes redirected to create a radiating artery along the institution’s walls that altered the very temperature of the space. Asher’s intervention highlighted the overlooked elements of the gallery environment (temperature) and reprioritized the site of art, now located at the entrance/exit rather than inside the galleries.

Michael Asher, Kunsthall Bern, 1992

Alan Ruiz, WS-K80X4, 2019. Electrical conduits connected to building’s power supply, 4 LED lamps, existing architecture, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Artist and 1708 Gallery. Photograph by David Hale

Similarly, Ruiz redirects electricity in orderly conduit raceways along the walls that feed into large LED safety lamps that resemble security lighting or those used in industrial construction. Mounted against the side of one gallery wall, the light is emitted unevenly, giving the exhibition space an eerie, unfinished feeling since the standard overhead lighting remains dark- an anathema to white cube exhibition standards that demand unobtrusive, uniform lighting. Sculptural steel vents on the floor make up Western Standards-LV1-4, these highlight the circulation of air and light between the gallery and basement space, or between exhibitionary and the storage/information spaces normally excluded from public view.

Alan Ruiz, WS-LV1-4, 2019. Stainless steel, existing architecture, 11.75 x 10.5 in. Courtesy of the Artist and 1708 Gallery. Photograph by David Hale

Additionally, Western Standards (Enclosures 1-12) is a series of vertical strips of glass mounted to the wall that obstruct and screen vision. Together, the alteration of light, air, and visual sightlines contribute to the deconstruction of neoliberal architecture, characterized by its ubiquitous employment of modernist steel and glass in order to contain and control bodies with the perception of individualist freedom and transparency.

Alan Ruiz, WS-E1 - 8, 2019. 1708 installation, Aluminum, hardware, glass, rubber. Each unit 8.5 x 1.75 x 24 in./ dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Artist and 1708 Gallery. Photograph by David Hale

Even more radical than the drastic alteration of the gallery space, Ruiz’s social activism takes the form of a lasting intervention into the daily operations of 1708 Gallery by requiring the gallery to become the first Richmond arts nonprofit certified by W.A.G.E (Working Artists for Greater Economy). W.A.G.E., established in 2008, is a national program that calculates minimum payment standards for artists, as such, it recognizes nonprofit arts organizations for committing and to and voluntarily paying artists these minimum standards. By obtaining this certification and its public guarantee of equitable pay, 1708 sets a standard for the Richmond Arts Community, from large institutions to city-sponsored projects. It is not enough to stage exhibitions that represent social and political subjects or exhibit diverse artists. Rather, it is imperative that arts organizations act by paying artists fairly for the work that they do, especially as artists are continually asked to contribute free or underpaid labor while bearing the costs of producing work and that of living. Infrapolitics renews institutional critique and social engagement with an urgency that goes beyond demonstrating social inequality or providing temporary art world versions of underfunded public services.[1] Instead, it demands the contemplation of the site, past and present, while also intervening in existing neoliberal financial models to provide an alternative to the prevailing systems of contingency and exploitation.

Infrapolitics is on view at 1708 Gallery through June 29, 2019.

https://wageforwork.com/home#top

[1] See Claire Bishop’s critique of socially engaged art in Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London and New York: Verso, 2012.

Rachel Hutcheson is an art historian with a focus on photography and new media art. She is currently a PhD student at Columbia University.